This is Creswell Crags, a gorge full of magnesian limestone caves, that were occupied during the Ice Age.

According to the guide, about 60,000 years ago (about the time modern humans were arriving in Australia), there were Neandertals living here, along with hyenas, mammoths and reindeer. Then it became too cold until about 15,000 years ago when modern humans took up residence.

This is the largest of the caves. The entrances we went into, complete with our hats with torches on them, is along a bit futher.

Even with a bunch of people with torches, it is still dark in the caves so the photos are a bit grainy.

Magnesium limestone does not form very big stalactites. You can seem some hightlighted on the right, and some occasional big ones like those at the back.

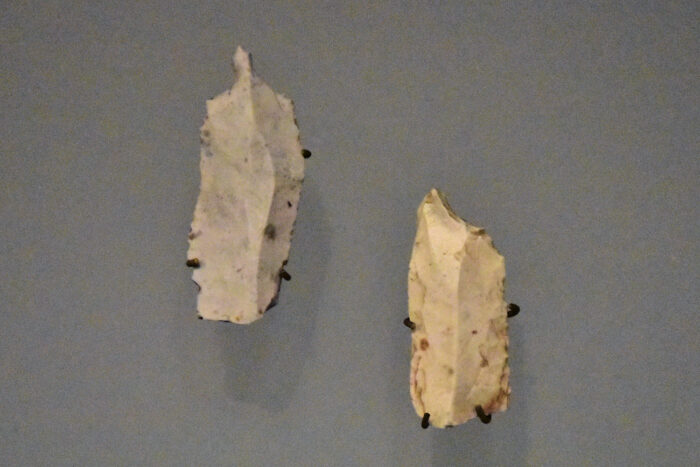

The guide talked about life in the caves and passed around replica flint knives and hardened reindeer antler. She also had this genuine, not-a-repliaca worked rock that, she said, has been found in many place but no one is sure what they were used for.

This tiny Victorian-created tunnels took us through to the back of the cave.

They don’t think anyone actually live in here, the guide said, due to a lack of artefacts found, but there were hyenas.

From their museum:

Hyenas sometimes swallowed quite large pieces of bone which they could not completely digest. While in the animal’s stomach, there fragments were corroded by the digestive juices, which smoothed the sharp ends, rounded the edges and pitted the surfaces with holes. If the fragments were still too big to pass through the hyena’s gut, they were regurgitated onto the cave floor. Many bone fragments found at Cresswell Crags look like this and show the caves were often used as hyenas dens for long periods of time.

We didn’t encounter any hyenas,

but we did come out with a woolly mammoth.

Alsp in the museum is a baby hyena skeleton

This is tiny. Just a few centimetres long.

Oldest coloured drawing known in Britain

12,500 years old.

With its chin up and mane flying, this finely engraved horse maybe be running for its life. Drawn on a piece of smoothed and polished rib bone, the horse’s neck is outstretched and its nostrils flared. You can see the closely engraved vertical lines of its thick, upright mare along the top of the bone.

There’s the head and muzzle of the horse.

A bone needle from the same period but also

the tools used to make it. A burin to cut off the fragment of bone (left) and a sharp pointed tool to make the hole.